An Interview with Abdul Raheem Salem

The artist in his studio. Courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

“It feels as if us Emirati artists were digging for stones in the ground in the later 1970s and early 1980s. Suddenly when you return from studying abroad filled with so much new knowledge, you suddenly find yourself again in a barren desert. Us artists were trying to make the desert grow trees and greenery in the arts; we wanted to make it a happy place for ourselves and the society to appreciate the arts at the same time. It was very difficult for us to change society so fast. We tried to grow slowly with the people to accept us and to understand what we do and what we think about, but it didn’t come easy.”

MEA: What is your artwork about?

ARS: After studying in the Cairo College of Fine Arts, Egypt in the late 1970s and returning to the UAE, I wanted to think of doing something different than other artists in the region. After over a decade of experimenting with different subjects, in 1992, I grew to become close with a folkloric character named Muhaira, finding myself drawing this woman in pencil, pastel and acrylic. The story of Muhaira is from a from local folklore I heard growing up as a child from my mother. Muhaira was was a slave living in a big family in Sharjah and while she would go to the market, a man would always try to flirt with her. She rejected him always and suddenly he used magic on her to make her crazy. I don’t know if this story is true or not but it has propelled me to dedicate my work to her.

A portrait of Abdul Raheem's mother. Photo courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

MEA: Were you able to see Muhaira?

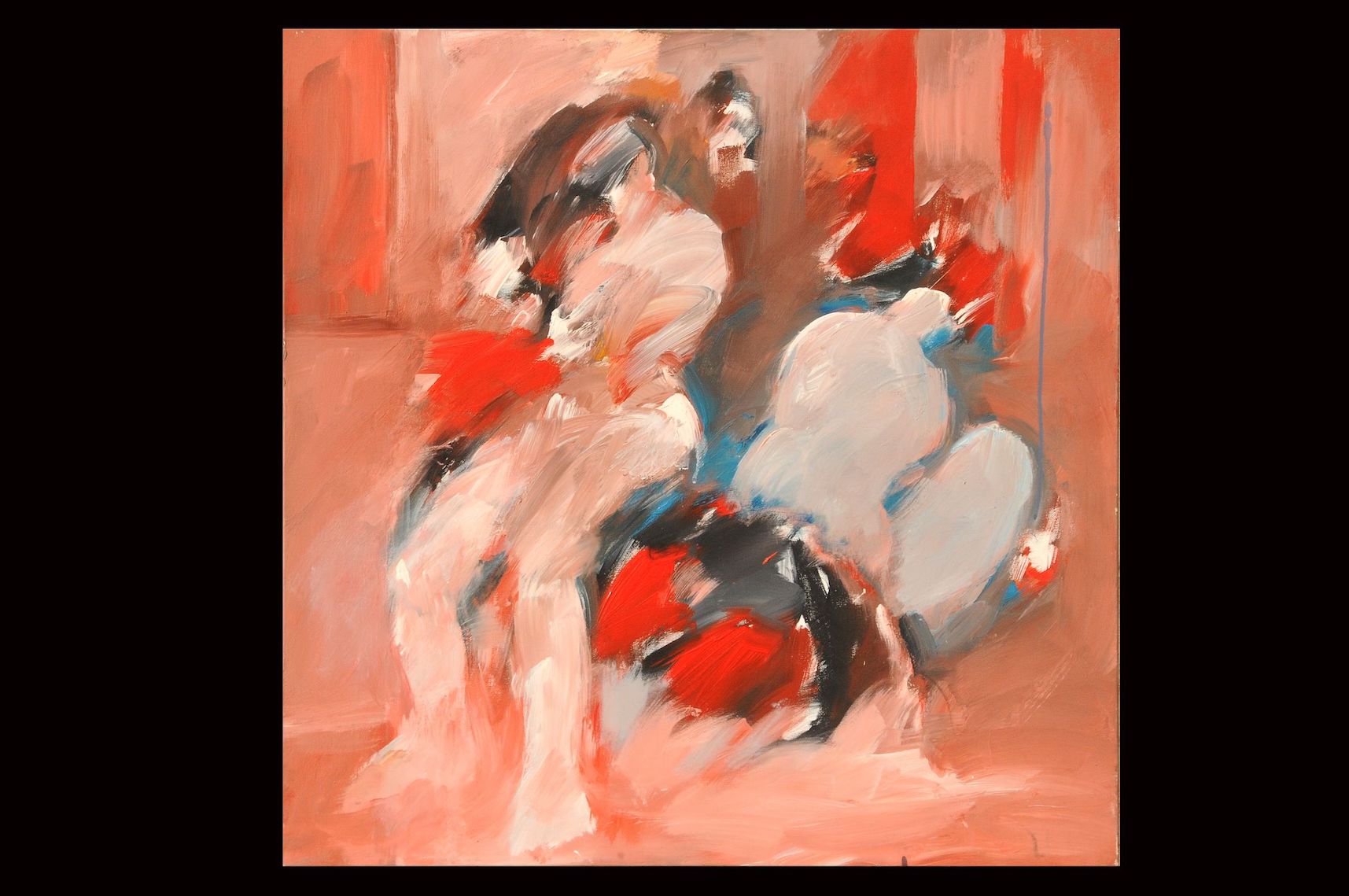

A study of Muhaira. Photo courtesy of Emirates Fine Art Society.

ARS: Yes, I have, in my dreams. She is a lovely and beautiful woman, married, with a child and usually she has many dogs around her. She visits a lot of houses but she has never hurt anyone. She heard me calling her and she told me because she rejected that man she lost her life from the curse inflicted upon her. She lost her relationship with her family and others, and she died tragically. She was living alone in a desert and made a small campfire and she died that way. I saw her sitting and walking in my dreams. I wanted to depict this experience of seeing her in my painting.

MEA: What would you classify your artistic style as?

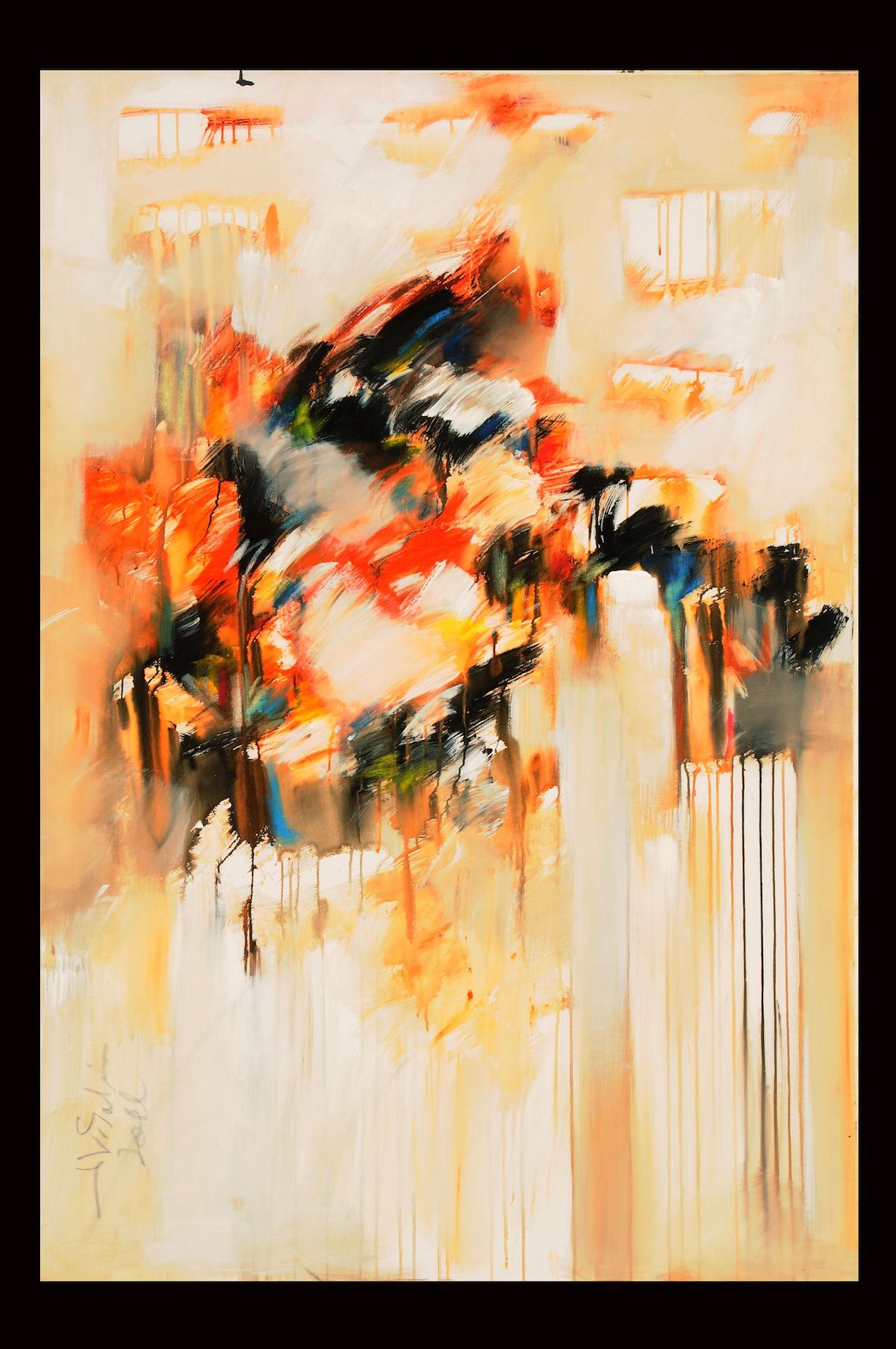

ARS: My work is similar to Futurist art, but I don’t believe the whole message of the Futurist group (1909-1944). My work involves considering motion through time. I measure the certain time interval from moving from Point A to Point B and I try to put in my painting this interval of time and movement within a two-dimensional plane. The lines go together, up and down with the painting. I need all of the painting to be tied together.

MEA: How do you apply this technique to the concept of Muhaira?

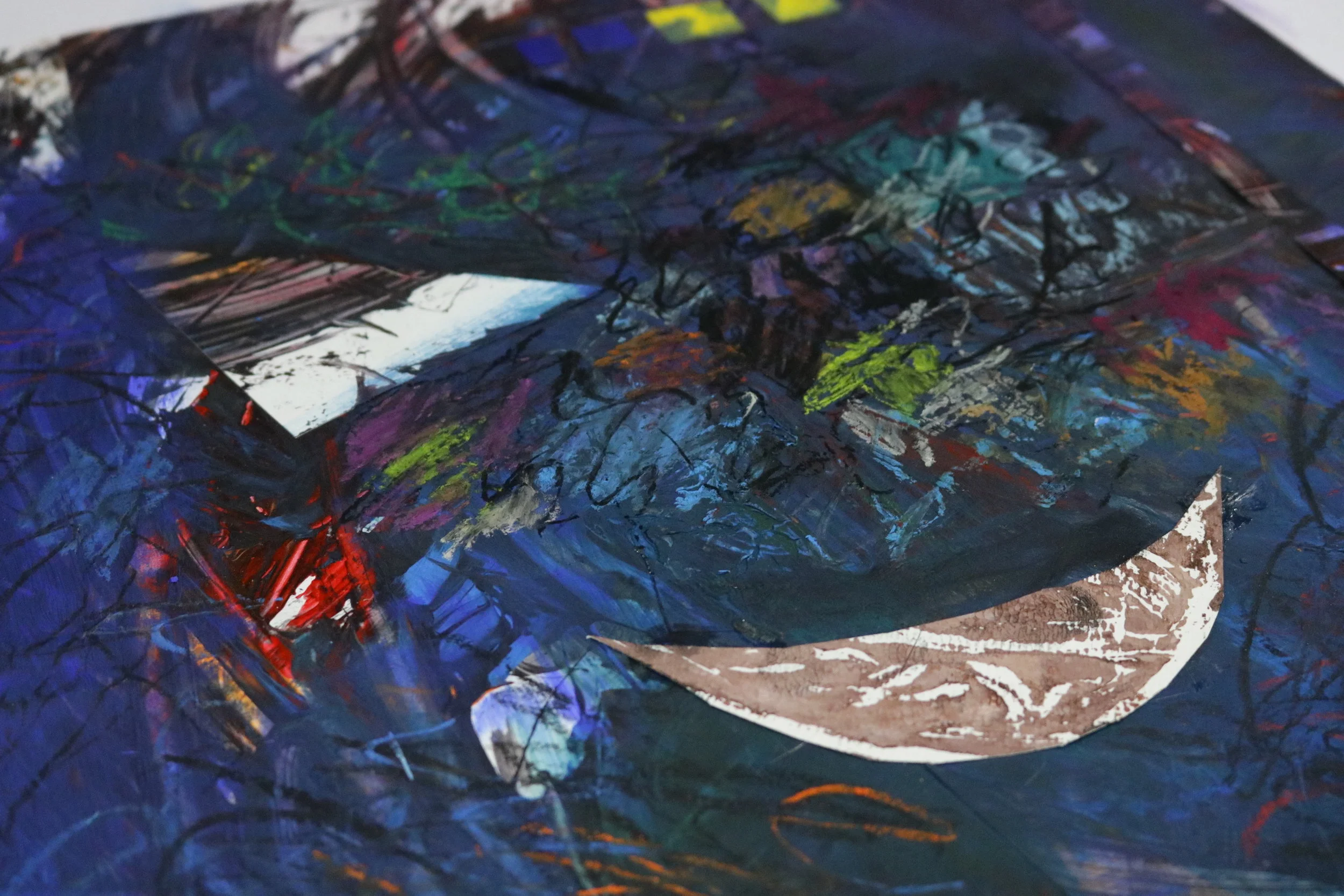

Creative collage. Photo courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

ARS: I focus on her shape with pencil and then I use pastel to do the figures of her. I use symbols like triangles and squares as a representation of her. Since most are abstracted versions of her figure, I want to show each person has their own internalized Muhaira, breaking free from society's expectations, but in a different way. Physically, Muhaira to some people could have long black hair, green eyes, tall, or short. I want each person to realize they have their own Muhaira and for them to contemplate what they think about when they see and experience Muhaira in my paintings.

MEA: Of the reactions to your work, do most people love this concept of Muhaira?

ARS: I am not looking for people to love my work. Love means being accepted. It means to have a part of this painting in your heart. It is a song for oneself. It’s not necessarily special for you, yet you think this song is for you because you heard it with your own ears. The pain you felt coming through a particular song is to make you feel dejected. Painting is also like that. I do it for myself but I do it for the people to see it. I don’t need to hear if the work is good or bad. I respect all those who view it but if people have a different level of education and thinking and say—'I see—oh I love that,' or 'I feel something inside that painting,' or I see eyes,' it bears no difference to me because it’s personal. It’s very sad when people say these things to me because it's totally abstract! I don’t put any eyes or nose into my works, but people try to find the key inside the painting to understand.

The artist in his studio. Image courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

MEA: So you have to experience the painting in its entirety.

ARS: We are complete in our entirety. I can’t explain independently about my kandoura or my ghutra (Emirati robe and headdress). It is me in complete person.

MEA: In Cairo, you were trained in sculpture. Why the transition when you returned home?

ARS: I didn’t change because of religion. For me a statue is too minimal. You cannot go deep inside the work to explain what that work has inside you and for the people to discover what you want to say. Painting filters through layers of color more than a statue.

When I talk about magic behind Muhaira, the feeling resembles Sufism. Sufism helps train your mind to delve into your spirit. A spirit cannot go into stone, wood, or a statue; it stops at the surface. In a painting, this experimentation is open. You can go deeper, skipping from Point A to Point B and return back to it. I can make 100 statues about Muhaira, that is no problem, however painting her allows a deeper connection, and the colors give you more feeling about what her.

MEA: Can you explain this further how a sculpture makes you feel?

ARS: Sculpture is like the water; you can see the water, only you can see one color—blue. Sculpture makes you feel stuck onto one color. Painting is deeper, you can go deep inside the sea, and you can see shells, small fish, etc..

MEA: You had your childhood in Bahrain. Would you credit the arts education in Bahrain helped you?

ARS: I lived in Bahrain until I was about 16. We had great art teachers in our schools, mostly Egyptian and Bahraini. They pushed me to open my eyes to draw, and to see the shapes. It is important for the youth to understand the shapes and the lines. In the 1960s, Bahrain had more functions with art, including exhibitions, lectures, workshops that were not in the UAE. In the UAE, the arts education started during the 1960s/70s drawing classes, however there were no major art functions. Only around 1970, was there some action. I remember once Hassan Sharif, Fatma Lootah, and Abdul Rahman Zainal had an exhibition at a library in Dubai. That was one of the first.

Abdul Raheem (left) with HH Sheikh Rashid bin Khalifa Al Khalifa (center) during UAE Art Week at Bahrain Art Society Center, approximately 1984-85. Photo courtesy of Emirates Fine Art Society.

MEA: When you went to Cairo, was that the first time you got to meet many of the other Emirati artists who studied there at the time? (i.e Dr. Najat Makki, Obaid Suroor, Dr. Mohamed Yousif, etc)

ARS: Yes, I only met them there in Cairo for the first time. I really didn’t think we had other Emirati artists at that time.

MEA: How important was Cairo to you?

ARS: I actually wanted to study in Paris or Italy. Most of my art teachers in the UAE were from Egypt so from that I liked Egypt. My time in Cairo gave me the chance to learn the art and history from them, and most importantly I discovered myself. Most of the times I would go to the museum and for some reason I was obsessed with ancient Egyptian clothes. They truly had these beautiful interwoven cloths and for a time I wanted to do a Master’s in comparing the Egyptian clothing to Greek and American clothing representations. These objects outside the classroom opened my eyes to see the things, not just the college itself.

MEA: What was a memory of College for you?

ARS: I trained with about 20- 25 students in the classrooms, and drew every single day. We would have to make statues from models and my professor always would give me a grade of 85. I felt like I was the best of all of them though. So I asked my professor why, since most students thought I was the best. He told me my work was good, but that I was seeing elements without feeling. I would draw clothes or skin in exact, with the same color and line, but he asked me specifically ‘how do you give me the feeling about these clothes?’, and I realized that was my mistake. I had to move more towards feeling. Then my grades went up!

MEA: How did the Emirates Fine Art Society come about during this time?

ARS: For the reason of not knowing these other artists while I was in Cairo, when I came back from abroad, all of us artists decided to make the art society together. It was our job to form a group of artists in the UAE to work together and teach younger artists.

First Annual Emirates Fine Art Society Exhibition, 1981. Photo Courtesy of the EFAS.

MEA: Any other early memories of its formation?

ARS: Mohamed Yousif started discussing with me about this in the last year of college. Because Mohamed was also working in the Sharjah National Theatre, he used this position as a way to contact with some other artists. We had the earliest meetings once we returned from Cairo at the Sharjah National Theatre, thanks to him. The Ministry of Labor required 15 persons to enlist an organization in the UAE, so it was up to us to get the signatures. We contacted with HH Dr. Sheikh Sultan bin Mohamed Al Qasimi, Ruler of Sharjah around 2 to 3 times. It was then myself, Hassan Sharif, Abdulrahman Zainal, Hussein Sharif, and Mona Al Khaja made the first group for the Art Society. Then a lot of younger artists came to us and we started to teach them.

MEA: What were the most important exhibitions you remember?

ARS: One of the most memorable was when we invited artists to the Arts Society in Sharjah from the Soviet Union in 1992, because it was a precursor actually to the Sharjah Biennale for us. In the early 1980s when we started, we only focused on artists in the UAE. After 10 years, I suggested for the art society that it was healthy to invite artists from outside of the country to our exhibition. Initially we focused on the Gulf since it was easier to manage, and every year we invited someone in our art society from the Gulf as part of our exhibition so we can create this exchange. We then expanded to the Arab countries and eventually we reached to the Soviet Union, even a very high person in the USSR came here to see the show.

MEA: So this lead in a way to the Sharjah Biennale?

Tashkeel Magazine, first publication, 1984. Courtesy of the Emirates Fine Art Society.

From that time we discussed with HH Sheikh Dr. Sultan the importance of staging a biennale, both in inviting international artists and the visitors from around the world that would follow. Originally our target focused on Arab artists living abroad, no one knew there was any art scene happening in the UAE, so in a way the Biennale was a way to show them. So we created prizes and we organized workshops and lectures along with our annual exhibition that had been going on since the beginning. Then HH Sheikh Dr. Sultan accepted this and the Biennale suddenly changed our careers onto the regional stage since then.

MEA: Was the EFAS produced ‘Tashkeel’ magazine very important?

ARS: Yes, during the time that we opened the art society, we published Tashkeel as a way to share the message about who we were and what we wanted to do. We focused on recruiting members, we taught lectures, we learned. As a way to introduce a semi textbook to the art society, we gave out Tashkeel for the members to read. We also allowed any person to write in Tashkeel. This was a major way some artists and writers developed.

MEA: Was that like the art history book?

ARS: Yes you could say so. If you saw the first one, we typed it and took a photo copy for the members. We started because we believed that the artists were important. We needed to teach the people to understand, love and appreciate art. All people in the UAE enjoyed art to an extent, but us artists needed to show society, and push them to understand more. Many times someone came to us saying they liked to draw and wanted to do something more with it, but they did not have a chance because what they studied or the society at the time didn’t encourage painting and making art.

The artist's studio. Photo courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

MEA: Do colors remind you of your past?

ARS: Yes, after I finish my work sometimes I feel the past. It can be very sad for me but I try not to let it affect me. Before when I came back from Bahrain with my grandmother in my late teenage years I didn’t want to be in Dubai because I wasn’t happy. It wasn’t about the place or the people. It’s like the feeling when your heart is not happy, do you sometimes feel that? When the place is not comfortable and such, this is what happened to me. Most of the time my mother would talk about my father, who died when I was very young. And they would put very dark black pictures all over the place in my house. I suppose, even if I don’t say it, this sadness of the past can come out into my painting. In painting I discovered myself inside the work.

Newspaper excerpts on Abdul Raheem. Photo courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

MEA:I’m sure you go through flashbacks with these older artists and the struggle you went through.

ARS: It feels as if we were digging for stones in the ground. And when you come here from studying abroad and filled with so much new knowledge and you find a total desert. Us artists were trying to make the desert have trees and greenery; we wanted it to be a happy place for us and the people at the same time. It is very difficult for us to change society so fast. We tried to go slowly with the people, for the people to accept us and to understand what we do, and what we think about. Art is important, it is part of the culture and for us it is like a light. We walked slowly. It was good for us and for the people. When artists like Hassan Sharif did art that no one could understand, it was very difficult. But over time after we did this painting, then society accepted it. We then did figurative painting. New artists would come and speak over time. It was easier for people to accept it. In Sharjah when we exhibited new art, people would see it, and it wasn’t like they were saying to us ‘no we want the old way of painting’ or anything like that.

MEA: In terms of the art society here, what do you think is missing? Is it the personal connection with the older and younger generations of artists?

Abdul Raheem worked with the Ministry of Education to produce children's arts books. Image courtesy of Suzy Sikorski.

ARS: The young artists we taught in the 1980s and 90s only had the art society to go and train in their studio. We tried to give them what we had and what we learned. Today the younger artists see the picture of his or her work in social media and they think it’s finished, they almost make it seem they don’t need the help or want to listen. I have been invited to local universities several times. To see the young talent is good but they don’t know me. I go there and we feel like strangers.